The Captain, the Storm, and the Stash

Posing as a fuel-hauling captain, Skinner smuggled drugs through Caribbean waters. One fateful voyage during a tropical storm nearly ended it all.

By the 1980s, Skinner had already been involved as an operative in multiple intelligence-related operations throughout the world. Under the auspices of HIDTA, Skinner was infiltrating cannabis and cocaine operations throughout the Caribbean while posing as a drug dealer. His friends back home knew nothing of his covert operations.

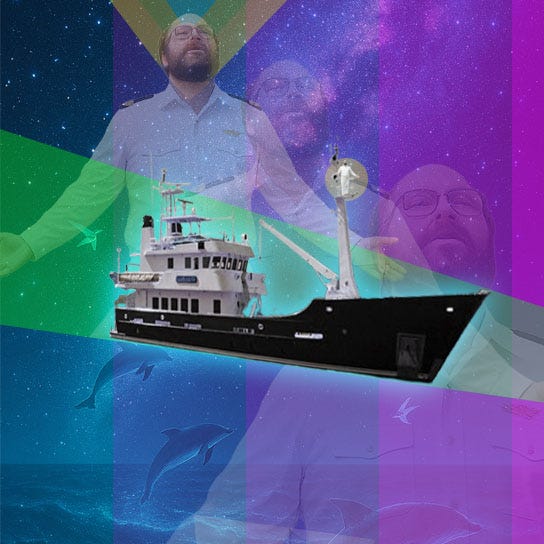

Captain Gerrard T. Finnegan operated the CB-1 standby emergency offshore mineral and oil vessel—or at least that’s what the U.S. Coast Guard thought. Although he went by P.C. Carroll1 in Boston, Skinner used the Finnegan alias on his captain’s license2. With the help of his friend, a retired two-star general from Arkansas named Moise Seligman, Skinner acquired the vessel and modified it to run as a miniature fuel tanker3.

Under the guise of captain, Skinner bought, sold, and transported fuel to various islands in the Caribbean. It was a side hustle that made moving drugs a cinch. Occasionally, he invited friends to join him on his nautical adventures. In May of 1988, Robert Chapman and a friend from high school, Scott Aitken, joined Skinner on a seafaring romp. Skinner told them he would pick them up in Freeport, Texas.

“The first day it was great,” Chapman recalls. “I mean, it was just cool. He was captaining the boat and showing me how to do stuff, and we had dolphins in the front and chasing the boat.”

Four days into the voyage, Tropical Depression One intensified and began moving eastward across the Caribbean Sea. The undaunted three-man crew continued southward through the Yucatan Channel, intersecting with the storm’s trajectory. Around midnight, an alarmed Skinner shook his friends awake and explained they were in danger: the boat was starting to list and he needed help pumping fuel in order to correct it. The groggy, swaying friends took directions from Skinner. Despite their efforts, the autopilot system overtaxed the orbital valve, taking out the vessel’s steering. Anxiety electrified the tiny crew.

“I was like, holy shit, red alert!” Chapman says. “We are in the dark, we are seeing fifty-foot swells and all we can do is go in giant circles. I seriously thought we were going to die.”

Longest Night Ever

Hoping to maintain the ship’s integrity, Skinner asked Chapman to secure the deck. Chapman grabbed a flashlight, strapped on a lifejacket, and clipped a rope onto the vest. With the boat heaving, and massive waves crashing over the vessel, he raced out onto the slippery deck and brought in loose ropes to prevent them from tangling in the propellers. Soaking wet and a bundle of nerves, he returned to his room, changed, climbed into bed, and strapped himself to the mattress. As the cabin bobbed, rocked, and spun in the dark, Chapman traced an exit path in his mind, then retraced it upside down in case the boat capsized. As he was going through the exercise, he realized the futility of his thinking. He was going to drown.

The sun eventually rose on the longest night of Chapman’s life, but the storm was unrelenting. Skinner suggested removing the auxiliary steering from the top of the vessel in hopes of stabilizing it. There were no mechanical tools available, so Chapman grabbed what he had. Using a steak knife and a screwdriver, Chapman began the Kafkaesque task of chipping away at the plywood base. Soon he was covered in sweat and hydraulic fluid. According to Chapman, Skinner realized they were stuck and finally sent out a distress call, and within an hour, a U.S. Coast Guard vessel showed up, cannons pointed4. The rescue ship sent a dinghy over to the stranded ship.

“The first thing one of those guys said was ‘what are you guys doing out here?’” Chapman recalls.

Earlier, Skinner had told Chapman that he planned to pick up 10,000 pounds of marijuana in Jamaica—but Skinner only told the Coast Guard that he was delivering fuel to the Cayman Islands. Eventually, the Coast Guard loaned the three friends tools to repair the ship’s steering system. While the men worked, Coast Guard crewmembers reviewed the ship’s paperwork and searched its cargo. When they ran Scott Aitken's passport and identification, they halted their search. Everything cleared inspection, including the 5,000 roles of plastic wrap Skinner had loaded into the ship’s hull. Nobody asked about them.

The storm traumatized Chapman so much, that once he reached Georgetown, Grand Cayman, he dined on little more than lobster bisque and alcohol. He told Skinner that he wouldn’t be getting back on that boat. Ever.

“He poured me on the plane the next day, and I flew directly back to Houston,” Chapman laughs.

Psychocosmic Cruises

Out there, on the open Caribbean, under the purring smile of a Cheshire moon, the whole vast sea was serenely illuminated. In Tucson and Boston, smugglers and narcs and double-faced agents scuttled around and entrapped each other, but out here there were no enemies to be made among the waves.

Skinner routinely made nocturnal treks between Cayman Brac and Montego Bay without a crew. On nights with a full moon, flying fish would flock above the surface, their wings flashing silver over the swells. When he reached a point where he had 30 miles of open sea, he would engage the ship’s autopilot, turn off every light—even the running lights—and climb on top of the wheelhouse.

“That’s about as illegal an activity as you can do,” Skinner says. “I didn’t care.”

Moonless nights heralded a spectacular sight. Surrounded by sublimity, Skinner drank mini-huasca shakes made of psychoactive anadenanthera pods. There, thirty-five feet above the waterline, he felt the sea lift him skyward into a heavenly embrace. Labyrinths within labyrinths gyroscoped the heavens above him, and as he felt himself entangled in light, he saw the past, present, and future intertwined.

Adrift alone, his heart soared into the night sky. Starfields gracefully manifolded overhead, and as the ship slipped through the waters, bioluminescent noctiluca, living phosphorous, burst into glowing green and blue swirls over the wet deck. Dolphins pirouetted before the craft, spinning in hallowed infinity. A majesty of diaphanous sea light swirled around the vessel in cosmic grandeur.

“I remember that the common theme on every single trip was You are on this planet for other reasons than to collect little green pieces of paper,” says Skinner. “I remember vivid lessons and experiences, and on a regular basis I was blending into the Milky Way.”

Paid subscribers continue below, where you’ll get to see one of the most bewildering developments in Skinner’s life story. You may have heard rumors about his work as an informant—but the ties go far deeper than you might expect. Your first peek will show proof of Skinner’s role as a HIDTA operative: The Olarte Affidavit, which foreshadows a much larger project involving the Medellin Cartel. Subscribers will also discover an upcoming cast of characters related to Skinner’s informant work.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Psychonaut Files to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.