America's True-Life Psychedelic Hogwarts

How a Catholic prep school in Tulsa, Oklahoma became a training ground for supertrippers

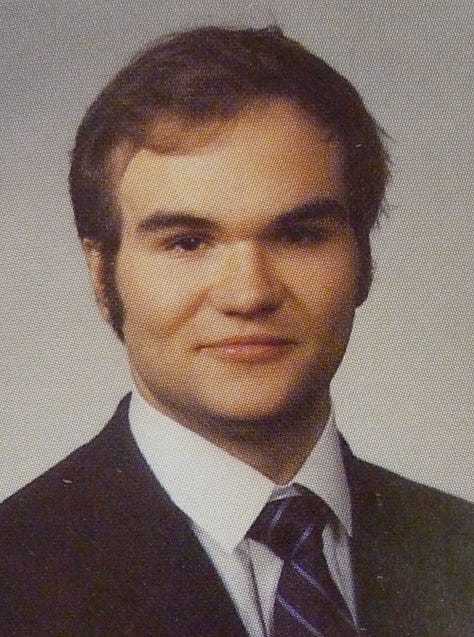

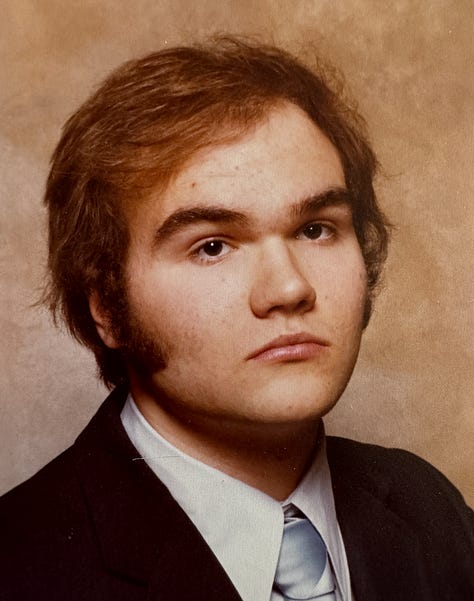

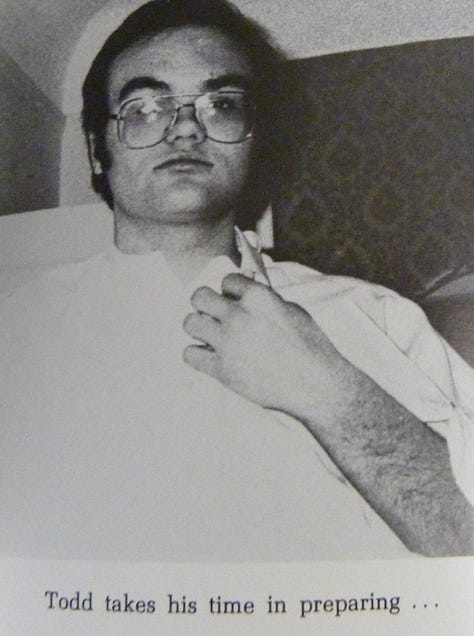

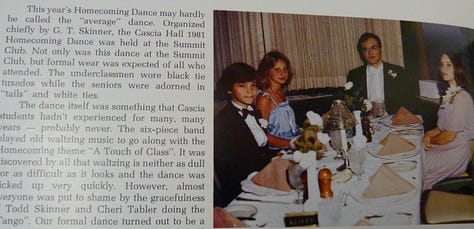

Built in the style of a French Norman castle and surrounded by forking paths, Tulsa’s Cascia Hall once operated as an all-boys academy, where worldly Augustinian priests attempted to rein in rebellious streaks fueled by Tulsa’s well-oiled elite. Back in the 1970s and 80s, it was the perfect place to push limits, and there was one student primed to test them.

Gordon Todd Skinner wasn’t your average kid. His mother bought him two of the first IBM computers and supplied him with personal tutors. A neighborly rocket scientist, Denis Zigrang, steered him toward science. Doug “Cousin Drug” Chasteen gave him a commercial-grade laboratory while he was still in grade school; of course it was used to manufacture and of course Cousin Drug taught Skinner lab techniques. Later, when Skinner was ten, his mother bought a $40,000 laboratory from Refinery Supply Company in Tulsa—a sizable expense in the 70s.

Around the same time, a science fair project on cosmic rays earned Skinner a ribbon; he did another project on the Doppler effect. Like thousands of others, he was charmed by Albert Einstein’s Autobiographical Notes, wherein Einstein imagined himself chasing a beam of light. Instead of dodgeball and bicycles, Skinner’s childhood involved beakers and floppy disks; his mental playground equipment included physics, chemistry, and computing.

But it wasn’t until Skinner started translating math into computer code that his obsessions began to merge and his imagination burst open. That’s when he began to doubt time.

If our brains create the illusion of progress, Skinner figured, then time must be composed of synapses, neurotransmitters, and oscillations. Skinner reckoned that memories of the past, present, and future must be constructs—merely stories we tell ourselves. Skinner thought back to all the convoluted conversations he had with Cousin Drug and wondered which chemicals steered those talks.

Yet all of Skinner’s brilliance couldn’t suppress the raw, physical confidence that was bristling just beneath the surface as he entered adolescence.

A Formative Fight

By seventh grade, Skinner was known to possess almost inhuman physical strength, and yet he detested sports—they didn’t compute.

Journalist David Goodwin, who weighed barely a hundred pounds at the time, still sounds incredulous about the day he faced down Skinner. Goodwin recalls him as a bully who relentlessly teased others, including himself.

In the locker room one day, Goodwin—who is African American—saw Skinner trip another kid and had enough.

Goodwin rushed Skinner and locked arms in an almost serpentine grip. Skinner wrapped him around a bench; Goodwin could hardly breathe. A teacher broke up the fight.

Although the attack left no physical marks on Goodwin, the thought still traumatizes him.

“Todd’s impulse to me was not a black/white issue,” Goodwin told me, “nor was my impulse toward him an issue of race or ethnicity. It was just that he was being mean.”

The incident not only terrified Goodwin, but it horrified Skinner himself, who had never before understood his own strength.

“I swore off violence that day,” Skinner says, recalling the incident. “Physical aggression nauseates me to the core.”

For the remainder of high school, Skinner committed no acts of violence or aggression, and Goodwin regularly joined him at the lunch table; he even attended one of Skinner’s parties.

In prison, Skinner has been stabbed, choked, and beaten on numerous occasions—one attack left him bruised all over and unable to raise his arms for months. He has never physically retaliated against anyone while imprisoned, according to records.

And yet Skinner stands accused of acts of horrific violence—acts that have fed endless myths about the man, despite the fact that he has never told his side of the story to anyone, not even to the courts who accused him.

Crucially, the fight foreshadowed Skinner’s belief that the human body could be pushed to its limits and survive—an attitude that drove him straight into his next obsession: so-called 'legal highs.' Ever the boundary-pusher, he was drawn to extremes like a moth to a flame.

The Most Dangerous Highs Are Legal

Several underground classics of the seventies shaped Skinner’s youth, but few as notably as Adam Gottlieb’s Legal Highs (1973), which offered a curriculum on mind-altering substances that spanned a range of psychedelics and deliriants.

“Don’t ever touch that book Legal Highs,” Skinner warns. “Just because it’s legal doesn't mean it’s safe—that son of a bitch is a bad book.”

As a teenager, Skinner worked through each listing, hoping to target the brain’s temporal processes. The first entry in Legal Highs reads as follows:

ADRENOCHROME SEMICARBAZONE -- 3-hydroxy-1-methyl-5,6-indolinedione semicarbazone.

Material: Oxidized eniephrine (adrenaline) with semicarbazide.

Usage: 100 mg is thoroughly dissolved in just enough alcohol, melted fat (butter), or vegetable oil and ingested. Because of its poor solubility in water these must be used to aid absorption.

Effects: Physical stimulating, feeling of well-being, slight reduction of thought processes.

Contraindications: None noted. Acts as a systemic hemostatic preventing capillary bleeding during injury. Adrenochrome causes chemically induced schizophrenia. Its semicarbazone does not.

Supplier: CS.

That particular misstep turned Skinner’s urine orange and delivered a violent headache. He swore off messing with his own brain, but grew curiouser and curiouser. He needed volunteers who would willingly open their mouths in exchange for any sort of high.

Skinner saw his Cascia Hall classmates as ideal vectors.

Teenage Experiments in Psychedelic Synthesis

When young Skinner needed chemicals or equipment, he’d call laboratory supply companies and place orders under the name of his mother’s company, Gardner Spring, Inc., and have the packages shipped directly to him. Their housekeeper, Barbara Elliot, recalls hearing him place an order for three chemicals used to make LSD, using his father’s charge card.

“They came, and I did check the names of the stuff,” says Elliot, “and it was in books about psychedelic drugs.”

Elliot estimates Skinner was in tenth grade then. She didn’t believe he had the skills to actually create the drug until she witnessed his labwork and saw the end result given to one of Skinner’s cousins.

“It was definitely LSD,” she says. Back then, LSD was so abundant and easily available that it didn’t hold Skinner’s interest for long. Elliot also recalls Skinner growing psilocybin mushrooms in the basement of his mother’s home using lamb dung (the best kind of dung, according to Skinner) as a substrate, but they, too, were an easy and cheap score.

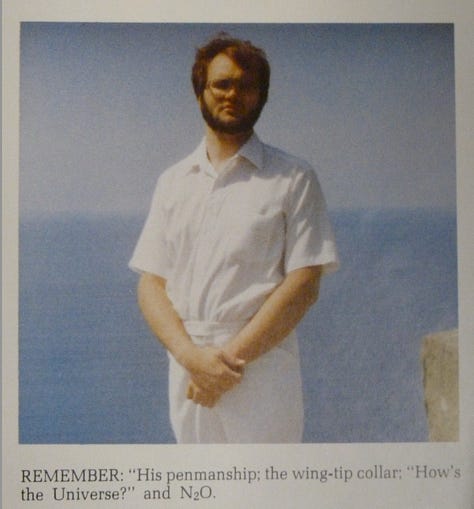

In addition to plenty of LSD, mushrooms, and nitrous oxide, dozens of exotic psychedelics flowed freely from Skinner into Cascia Hall’s corridors.

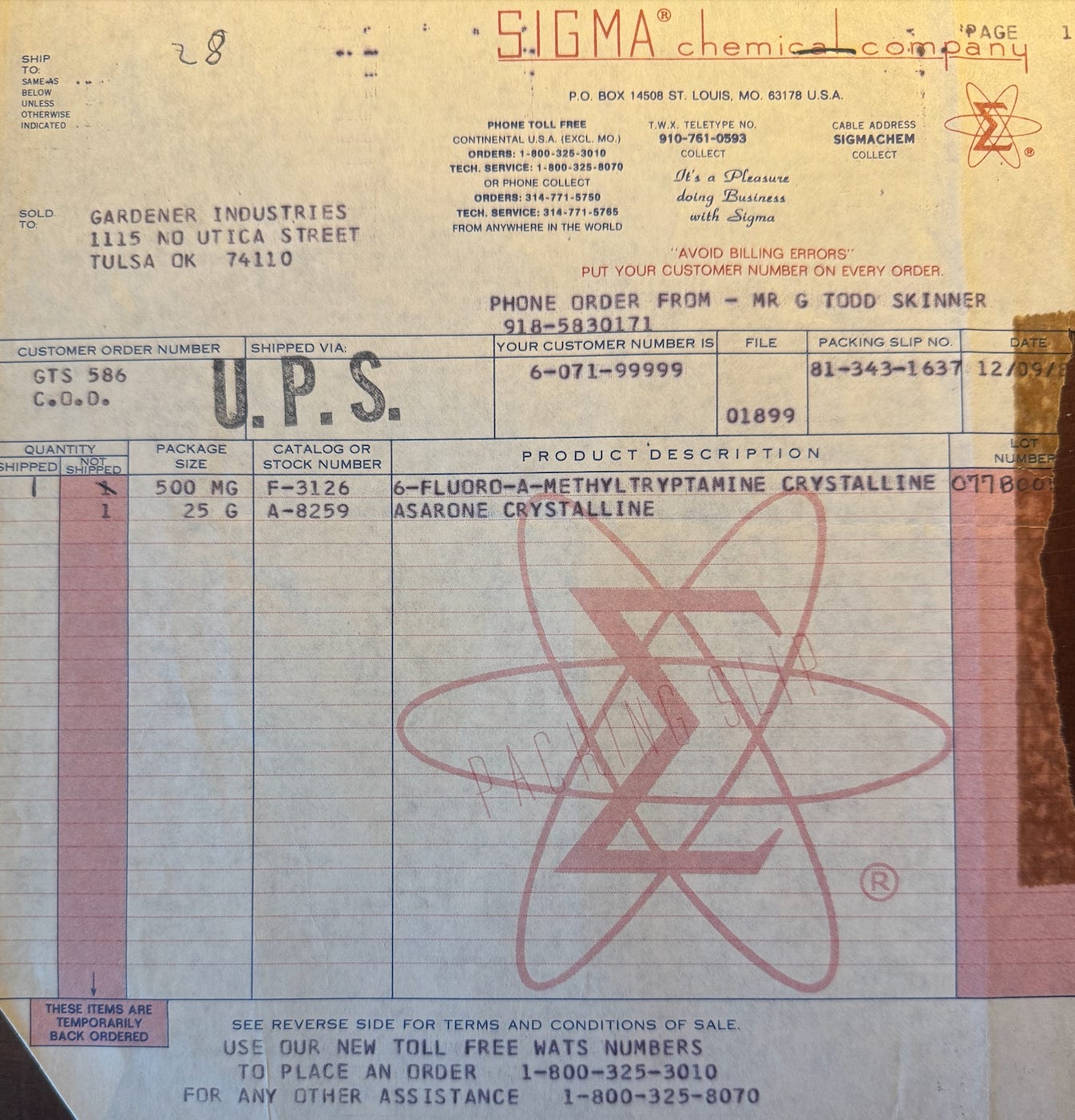

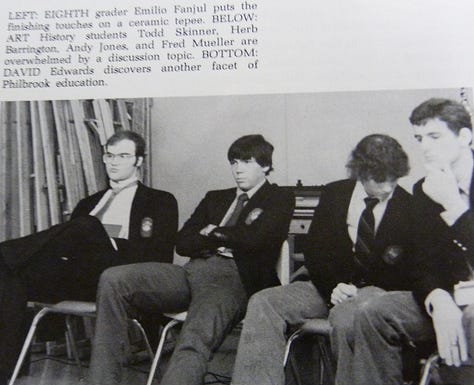

Back then, many exotic psychedelics weren’t prohibited. Skinner simply offered his father’s chiropractic license on order forms. In middle and high school, he ordered numerous chemical standards from Sigma Chemical Company, which allowed him to compare the validity of his at-home synthesis. In one interview, he recalled ordering 100 grams of alpha-Ethyltryptamine (AET) long before it became a Schedule I drug.

Soon, drugs had become so normalized at Cascia Hall that many students just reckoned they were available in every high school.

Elliot began to see herself as something of an older sister to Skinner. She felt an obligation to keep quiet and not ask too many questions.

From Chemical Roulette to Fifth-Dimensional Revelations

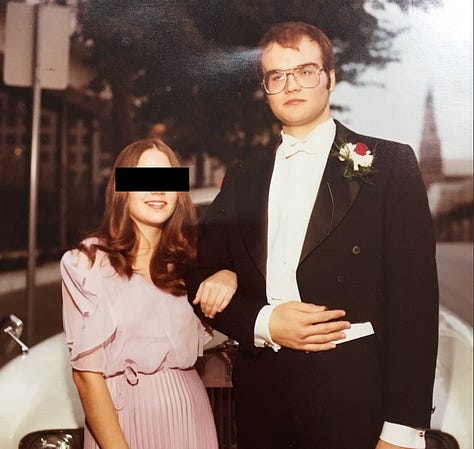

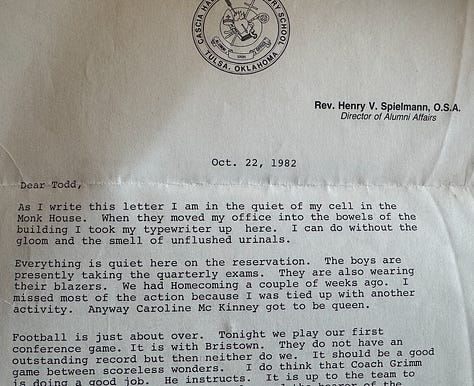

George Reyes was a junior-year math whiz who was so advanced he occasionally taught Fr. Hamill’s senior-level calculus class at Cascia Hall. A Filipino student who boarded on campus, Reyes grasped the conceptual world of matrices and multiple dimensions. He had never traveled to another dimension, however, until he intersected with classmate Gordon Todd Skinner during a “mini-mester” break in January of 1982.

Reyes and a friend approached Skinner and asked what sort of chemical-related fun could be had. Skinner suggested a new treat: 6-fluoro-alpha-methytryptamine [6-fluoro-AMT], an exotic synthetic compound that Skinner first acquired by simply ordering it.

Skinner had never known anyone to take 6-fluoro-AMT, so he ran a blind: he gave one boy an actual dose and gave the other a placebo. In this game of chemical roulette, Reyes took the hit. Despite Skinner’s warning to steer clear of certain foods, Reyes had reportedly gorged himself on cheese enchiladas following the ingestion of the drug.

In the late-night onset of the 6-fluoro-AMT trip, Reyes brushed off concerns that he was high. But early the next morning, friends heard a ruckus coming from the hallway and rushed out of their rooms to find a frenetic Reyes zig-zagging up and down the halls, his clothes slimed with chunks of regurgitated enchiladas. He was mazed within a maze of amazement and terror. Concerned by Reyes’ frenzy, one student did the only thing that seemed sensible: he knocked Reyes out cold, wrapped him up in blankets, and then took him over to Skinner’s house, where Reyes regained consciousness.

“He was like a raving lunatic,” another classmate recalls. Cascia Hall administrators called Skinner’s home and tried tracking down Reyes but couldn’t get any answers. Later, Skinner showed up and observed Reyes.

“Explain to me what you see,” Skinner asked him.

“Fifth dimension! Fifth dimension!” yelled Reyes. Skinner knew that tripping or not, Reyes wouldn’t have chosen those words haphazardly—he was brilliant at math and geometry and knew full well what he meant. As Reyes maffled about pasts and futures and folded his mind in and around dimensions, Skinner realized he had found the class of substances that targeted and disrupted the brain’s spatiotemporal-binding algorithm[1]: tryptamines.

Following Reyes’ 6-fluoro-AMT trip, Skinner had a chance to ask Reyes his impression of the experience. Reyes, according to Skinner, was adamant that he was jumping through dimensions during various points in the trip, and felt as though he could move between the fourth and fifth dimensions. As an example, Reyes claimed he could focus on his American Express billing statement and flip forward months ahead to see what his expenditures would be for the remainder of the year. He also claimed that he was able to “step outside” of the days and years [2].

Observing Transformations and Expanding Minds

Reyes’ stories fascinated Skinner and fueled his desire to engage in more psychedelic experimentation. He regularly offered doses to friends, curious to hear their reports. One boy took an usual tryptamine, approached a mirror, disrobed, and stood aroused, almost catatonic, for hours. Another reported he could time travel to Nazi Germany or the Civil War. Apart from the occasional tug from a nitrous-oxide-filled balloon, Skinner wouldn’t take the psychedelics himself. He preferred to stay on the outside of the trip, probing for more information about what his friends were hearing, feeling, and experiencing.

The guinea-pigging of his friends continued through high school and past graduation. Skinner says that he began to realize that his role as an observer was skewing his investigation. His friends knew that he would be asking questions about eternity and dimensions and might unintentionally alter their answers in an attempt to please him.

All the while, Skinner privately marveled at the changes he saw in his friends who took psychedelics. They struck him as more fluid and broadminded, and they reported improvements in their schoolwork. Skinner recalls that even Reyes was grateful for the aftereffects. Over time, many of Cascia’s students earned a reputation for being able to handle doses that far exceeded recommended amounts, and they learned to navigate the psychocosmos with a certain ease and confidence. They didn’t realize they were rapidly becoming major-league trippers.

One friend recalled that Skinner was so convinced about the positive benefits of psychedelics that he planned to commit the remainder of his life to expanding the consciousness of the planet by making them so abundant they could be accessible to all. Skinner had just turned 17.

For more extraordinary stories on the secret psychedelic history of Tulsa, please support the Psychonaut Files by subscribing below:

1] Neuroscience has taught us a concrete and humiliating lesson: we cannot trust our perceptions or our memories. Our brains will misidentify colors in a crowd, dispose of information that it deems unhelpful, and bend recollections to suit a story we want to be true. When it comes to processing the temporal, we only dimly understand how our brains behave, and we know that our processing results in illusions and outright errors.

“The days of thinking of [it] as a river—evenly flowing, always advancing—are over,” writes neuroscientist David Eagleman, who runs the Laboratory for Perception and Action at the Baylor College of Medicine. “[Temporal] perception, just like vision, is a construction of the brain and is shockingly easy to manipulate experimentally.”

Not all similar illusions are easy to duplicate. Eagleman’s lab dropped subjects from 15 stories and monitored their perception of temporal dilation.

Eagleman and other neuroscientists posit that the experiences are well-coordinated dance between different areas of the brain as they process both sensory input and its features (e.g. color, odor, pitch), which hit the brain at various speeds, and then reconstitute them as an integrated perception of the present moment. The experience of living, Eagleman suggests, is something like watching a live feed on television, where we know there’s a built-in delay that allows for editing. In essence, our perceptions may be little more than a consensus formed among different parts of our brains.

One of the brain’s most mysterious attributes is its ability to establish that consensus, what neuroscience calls binding. In a paper called “Binding by Synchrony,” Dr. Wolf Singer of the Mack Planck Institute for Brain Research theorizes that binding involves the brain’s electrical system.

“The brain is a highly distributed system in which numerous operations are executed in parallel and that lacks a single coordinating center,” Singer writes. Researchers speculate that the brain is somehow collecting information and packaging it electromagnetically as an experience that we interpret as the present moment.

Most of today’s spatiotemporal binding research (including experimentation in the field of psychophysics, the study of relationships between physical reality and perception) amounts to a comparison between perception and externally-measured, non-relative, rigid Newtonian physics. But ever since the advent of quantum mechanics, our scientific notions have undergone an unraveling. Out on the zeitgeist of theoretical physics stand a cadre of scientists—Julian Barbour, Heinz-Dieter Zeh, Hugh Everett III, John S. Bell, and John A. Wheeler, to name several—who champion a cosmology where space and even motion are suspect.

[2] Other friends of Reyes claimed that he was angry about the psychedelic experience because it came close to jeopardizing his education. Reyes died in his middle adult years, according to former classmates.